Dogmatic – Traditional – National

Analysis of the roles of dogma and of doctrine in the Armenian Church explores her traditional and historical foundations, including the historical gains and losses that have accrued to the church and to the faithful.

Rev. ZAVEN ARZOUMANIAN, PhD

Tradition and History

In generalthere exists the tendency to disqualify the role of the Church when the term tradition is attached to it, and for that reason tradition must be identified in its historical context. It seems complicated and controversial when distinguishing the essential traditions from thesecondary ones, labeling them non-pragmatic and easily unacceptable.

First and foremost it is important to apply “tradition” in relation to the Armenian Church in its proper sense as “history received orally” when letters and literature did not exist until the 5th century, while the Church existed in Armenia and functioned from the first year of the 4th century for sure. Here lies the basis of evidence whether we should abandon the “hearsay” tradition against the “documented” information. Tradition in its positive sense stands for “history transmitted and received,” and later recorded by our earliest historians.

To be sure that the religious and national aspects of the Armenian Church are formed biblically, historically, doctrinally, and ecclesiastically both by way of received traditions and recorded documentation. Together all of them comprise a standard touchstone, as well as a point of departure, to admittedly qualify the status of “the traditional made historical”. In the process they complete each other rather than challenge each other.

We also bear in mind that historic precondition sometimes simplifies our inquiry, and sometimes complicates it more, leaving no choice but to constantly refer to the parallel development of “traditional” and “national” phases of our Church, since both have proven to be the constitutional and the administrative dimensions for the Church’s persistence in Armenia as Hayasdanyayts Yegeghetsi (Church of the Armenians,) exclusively for the population of Armenia.

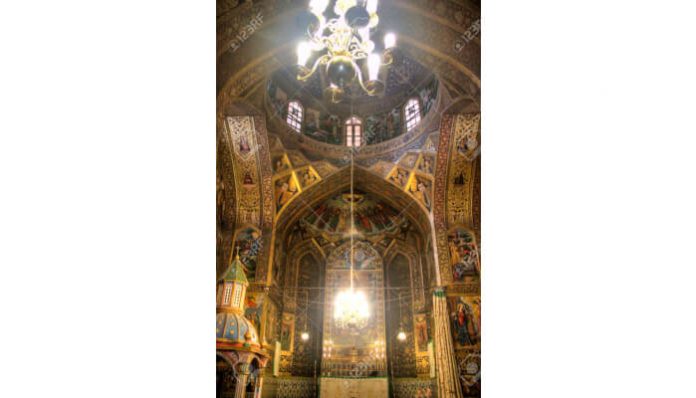

The First Church among Nations

It is universally recognized the Armenian Christianity the first adopted as a state religion in 301 AD. Priority is always given to the religious aspect when Christ descended to appear in the land of Armenia as a token to the first Saint, Gregory the Illuminator, who suffered gravely by the Roman Emperor and his vassal the King of Armenia, for not abandoning the new religion. He was saved and Christ appeared, the Armenian nation converted, and Gregory became the First Servant of Christ in Armenia. Thus far the data are traditional as said above, since the following one century testifies the Church’s recovery by way of tradition, supported by ancient Greek and Latin historians’ evidences wherever applicable referring to the existing Christianity in ancient Armenia. The “received” tradition was written by our first historians Movses Khorehatsi, Agathangelos, and Yeghishe Vartabed.

Peculiar for the Armenians

While there is not the remotest danger of alienating the Armenian Church from the Holy Bible, and from the One, Holy, Universal, and Apostolic Church of Christ as pronounced at the First General Council of Nicaea in 325, there is by necessity and as a matter of course her national identity which in the process has made her both historic and authentic.

In order for tradition to be valid in terms of today’s standards, it should prove to be meaningful and logical, rather than pleasant and expedient, initially commensurate with the Bible and its teachings. Trying to examine the history of the Armenian Church we shall see that both her existence and service were mutually supportive in the expression of faith, doctrine, and education. All three have subscribed to the meaningfulness and to the essentiality of certain traditions as indispensable factors within the constitution of the Armenian Church.

From Traditional to Theological

Three main issues are important for the reconciliation of the Armenian Church with her bona fide traditions while the traditional gradually developed into theological.

(a) Traditions of dogma and doctrine universally adopted by the First Three Ecumenical Councils and relative to the Canon Law that explore meaningful contribution to the validity of the foundation of the Armenian Church.

(b) The scrutiny and critical examination of national traditions of the Armenian Church relative to the Canon Law, and their value as vehicles for carrying on the existence and the efficiency of our Church. Concurrent with it the use of language and symbolism in Liturgy must be considered.

(c) The national parallel to the traditional in the life situation of the Armenian Church, always in accord with the Holy Scriptures on the originally translated text by the 5th century Translators. Soon the “traditional” became “theological” by way of philosophy and hermeneutics.

When asked where the authentic faith was to be found, the answer is clear and unequivocal: in the Person and teachings of Jesus Christ, the Son of God and His Gospel. Here again tradition helps as with a continuous stream to explain and elucidate the primitive faith, illustrating the way in which Christianity has been present and understood in the past. Tradition is therefore loaded with necessary and sufficient doctrines, accumulated by the wisdom of the past, meaning the doctrines of the Person of Christ, the Holy Trinity, and the status of St. Mary Mother of Jesus.

The Language Barrier

The Armenian Church’s authenticity is also confirmed by the tradition par excellence of her language, namely, the Classical Armenian dialect. We realize on the other hand that languages are means of communication and understanding. It must be clear however that there is no alternative but to keep the language as it is given the composition of the texts of the Liturgy and the Hymnbook. Music and text are tightly interwoven. Translation for education and learning the content of the books is most welcomed and truly expedient, but never for performance at which time the Armenian Church loses her identity and eventually her existence. Sacraments are partially performed in local languages, the Sacraments of Baptism and Wedding for example, only partially, not forgetting that the validity of the Sacrament is guaranteed by its originality. It is strictly forbidden by the hierarchy to perform the Divine Liturgy in translation, even partially.

One observation is important at this point. We are told constantly that why the Roman Catholic Church and the various Orthodox Churches have adopted the vernacular of corresponding nationality for their respective countries in place of the Latin and Greek originals. The answer is obvious. Those churches are serving in their own individual countries, America, Great Britain, Spain, Germany, along with their local Anglican, Episcopalian, Lutheran churches, and naturally local languages are used for the Roman Catholics and the Orthodox churches. The Armenian Church has one country and one option with the diaspora, where they try to preserve their identity. Understandably those millions living outside Armenia speak largely local languages and try very hard to operate schools around their churches and in the community.