April 17, New (Gregorian) Calendar

April 24, Old (Julian) Calendar

Rev. Zaven Arzoumanian PhD

Two Calendars

In this 2022 year the Armenian Church will celebrate Holy Easter twice, on April 17, and on April 24, one week apart, and some years as long as five weeks apart. It also happens that both celebrations fall on the same Sunday.

Question is raised as to why the difference, and why celebrating twice, especially when pilgrims who will travel to Jerusalem for Easter on April 24 will have already celebrated the Feast in the United States a week earlier on April 17. The distance between the two is variable, given the year, and the New and the Old Calendars that observe Easter Sunday accordingly, from one to five weeks distance between them, and once in a while the celebration coincides on the same Sunday, all depending on the calendars’ solar system on which the observance of Easter is established by the first Church Ecumenical Council of Nicaea in 325 AD.

This sounds confusing, but the simple and not quite adequate answer is the use of either the New (Gregorian) or the Old (Julian) Calendars. The canonical resolution of the date of Easter to be sure comes from the First Council of Nicaea.

What did the Church Fathers establish?

What did the Church Fathers establish at Nicaea in the first place? Based on Biblical evidences they resolved that Easter, the most important feast of the Church, the Resurrection of Jesus Christ, should be celebrated “On the first Sunday succeeding the full moon, right after the spring solstice.” The decision is equally applied by both calendars, and not that one has honored it and the other not as some think.

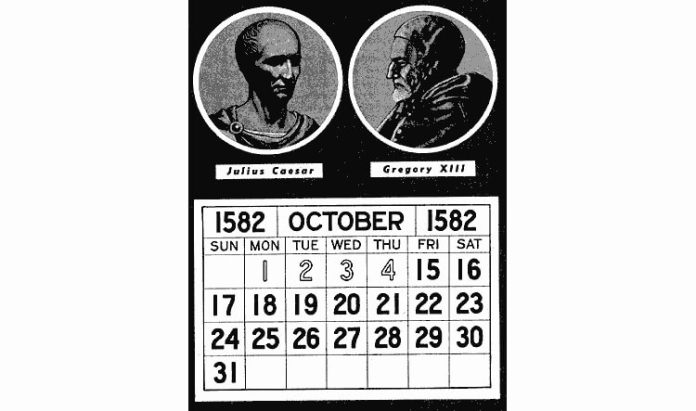

The problem in fact lied in the exact calculation of the days of the year. Note however that the Old Calendar which was proclaimed by Julius Caesar before Christ in 46 BC, and called after him, could have no bearing whatsoever on Christianity let alone on Easter. The Julian Calendar was purely secular calendar while the New Calendar which was prepared by Pope Gregory XIII (1573-1585) in 1582, and called after him, had the express purpose to calculate the days of the year correctly, by revising the Old, and establishing Easter Sunday according to the resolution of Nicaea.

The Problem

The problem therefore lies not in the accuracy of the one over the other, but in adjusting the exact days of the year by minutes, and then applying it to establish Easter Sunday correctly. The adjustment completed in the 16th century by scientists under Pope Gregory XIII as said above and the western churches gradually adopted it. Soon the Church of England followed the New Calendar in the 18th century and celebrated Easter with the Latin Church.

The Orthodox Churches hesitated for political considerations and stayed with the Old Calendar, but the Armenian Church was the first among them to adopt the New Calendar, albeit much later in 1923, by the Encyclical of Catholicos of All Armenians Kevork V Soureniants. With the exception of the Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem and the churches under its jurisdiction, for the important reason to keep up with their rights and privileges in the Holy Land, the Armenian churches all over celebrated Easter according to the New Calendar ever since.

Following the 1917 revolution of the Bolsheviks and after the fall of the Russian Empire, the communist regime adopted the New Calendar with the Russian and Georgian Orthodox Churches agreeing with the decree, but before the end of the year both churches reneged and turned to the Old Calendar. The Armenian Church stayed firm since 1923 ignoring the uncertain move of both churches. This confirmed the independence and the self rule of the Armenian Church from the orthodox churches, disregarding at the same time the political factor, despite being in the same region and under the same regime.

The Greek Orthodox Church and the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Constantinople being cautious stayed away from the use of the New Calendar for political reasons trying not to jeopardize the Ottoman Empire’s risky relationship with the Russians. As of today the Greeks adhere to the Old Calendar in Jerusalem.

The Calculation

Ordinarilythe Old Calendar calculated 365 ¼ days for the year which did not represent an accurate and final number, because the complete year calculated accurately 11 ½ minutes less than the above figure, which in 900 year period resulted in a difference of 10 days. To correct the mistake scientists made an unusual jump in 1582, and counted October 5th as October 15th, thus “balancing” by “elimination” the ten days of the year for the sake of absolute accuracy. This was what the New Calendar did, establishing and calculating 365 days for the year, and once every four years adding one day to the month of February and creating the “Leap Year” with February 29.

Those churches which followed the dates of the Old Calendar refused to accept the “correction” and stood behind by 11 days in the year 1700, 12 days in 1800, and 13 days in 1900. This is why the feasts observed on fixed dates according to the New Calendar, such as the Armenian Christmas on January 6 and the Presentation of the Lord to the Temple on February 14, are 13 days earlier compared with the Old Calendar. Bear in mind also that those fixed dates are counted in the Old Calendar just the same, January 6 and February 14, which in the New Calendar “reads” January 19 and February 27.

The Armenian Church

As stated above the Armenian Church started using the New Calendar since 1923 for the churches outside Jerusalem. The case in the Holy Land has been unique in the sense that three denominations the Catholics, the Greeks, and the Armenians have equal rights and privileges in keeping the holy shrines by the power of the decrees granted them from the 7th century. In Jerusalem the Armenians and the Greeks use the same Julian calendar, and sometimes the feasts coincide with unnecessary “confrontations.”

THE FORMATION OF

THE ARMENIAN CHURCH

IN THE FIFTH CENTURY

The Church of Armenia emerged as the genuine Church of the Armenian people only following the invention of the Armenian alphabet in 404-406 AD. The Church founded by the Apostles, and later formally established by St. Gregory the Enlightener, lacked two major and most essential factors, the Armenian letters and the translation of the Bible into Armenian.

Introduction

This study will cover the gap as well as the ultimate functional formation of the Armenian Church from the end of the 4th century to the end of the 5th. It is an attempt to treat transition of the church from the apostolic era to that of the literary expression of the established church in Armenia. All will fall under political hardship and sometimes under prosperous conditions, and yet the newly established church will survive all odds, given the God-given gift of all times, the letters and literature, through which not only the Holy Bible became «Armenian», but also the church was truly converted into an authentic Church of Armenia.

Three prominent leaders stood behind this great enlightenment: St. Sahag the Catholicos (387-439), whose long and productive pontificate as the Patriarch of the Armenian Church yielded much fruit in terms of the translation of the Holy Bible into Armenian, St. Mesrob Mashtots (born 362-440), a cleric who invented the Armenian authentic letters, opened the first schools in Armenia, gathering the first Translators to translate the Bible and the earliest liturgical books, and King Vramshapuh of Armenia (389-414), who sponsored the entire literary work involved in the enlightenment of the Armenian nation. All three accomplished the most essential task of literacy, especially when Armenia lost its political stability and was divided between Byzantium and Persia in the year 387.

The Armenian Alphabet

The Armenians rightfully proclaim the fifth century as the «Golden Age» for their nation, because at the dawn of that century a complete series of 36 Armenian letters were created by a talented priest Mesrob Mashtots in the years 404-406 AD. The task was an indispensable and a huge task that needed skill, knowledge, patience and prayer. Mesrob actually formed those letters after intense investigation of the Syriac and Greek letters. Independently from the above alphabets, he actually invented one letter per each sound in the spoken language of the people, who spoke the Armenian for centuries before but never wrote a single word for the lack of the letters. Mesrob, due to his deep concern for the literacy of his people, found it most necessary and, as his biographer and the first historian of the Armenian nation Goriun Vartabed relates in his Life of Mashtots, designed each letter to correspond to each sound distinctly and clearly. He was not satisfied with his first designs, but went to Edessa to have the letters reshaped and dignified by a calligrapher.

The translation of the Bible

Returning to Armenia, Mesrob Mashtots presented his 36 Armenian letters to his superior, the head of the Church Catholicos Sahag, who received him and the divine gifts with gratitude. Being himself a great scholar, now that the letters were available, the Catholicos embarked on the greater task of the translation of the Bible into Armenian from the Greek Septuagint text, brought into Armenia from Constantinople by the first students of Mesrob, who were sent to learn both the Greek and the Syriac languages in Edesa, Alexandria, and Constantinople. It took them some 30 years to accomplish the monumental work, while both Sahag and Mesrob were still living. Sahag died in 439 and Mesrob a year later in 440. Later the Armenian version was acclaimed by foreign scholars as the «queen of the translations» of the Bible, following which historiography bloomed in Armenia, schools were opened, and the immediate liturgical texts for worship, theology, and commentary of the Bible were translated into Armenian, basically from the Greek language.

Thus, the Armenian Church was genuinely founded and supported, this time by written literature and documentations, rather than political power. The church was invested with spiritual and intellectual wealth which potentially yielded the greatest cultural achievements for posterity in term of literature and arts. Bear in mind, as said above, Armenia had lost its political power, and in 428 AD, right in the middle of the Translators activities, the Arshakuni dynasty fell, and Persia dominated our land by marzpans (governors). Armenia, on the one hand, lost its earthly throne, but became eternally enriched by spiritual and cultural wealth to elevate our nation yet to a much higher and imperishable pedestal, the throne of total revival and survival as the people of God.

Resistance and Defense

The newly formed church in Armenia with its authentic alphabet and Bible was forced to meet the challenge of survival by defense of force against the neighboring Persia. The Sassanid dynasty, which came to power in 226 succeeding the Parthian dynasty, worshipped the fire, Zoroastrianism being their religion, and did not tolerate a Christian nation next to them, especially because of Armenia’s Christian ally, the Byzantines, who were real threat to Persia. The same tension had already partitioned Armenia in 387 into two between the two empires, the larger part under Persia in the east, and the smaller portion under the Byzantines in the west. Following the partition of our land, the Armenian kingdom ended in 428, and religious persecutions took their course. Persia threatened Armenia to abandon Christ and adhere to fire worship with total subjection to the Iranian power against Byzantium.

This happened right in the middle of the fifth century when the biblical, religious, and cultural awakening had just originated in Armenia with great enthusiasm. There was no choice for the Armenians, other than to defend their land, their identity, and equally their Christian religion. In 451 the General of the Armenian army Vartan Mamikonian, along with the ministers and the leaders of the church had to plead and tell Persia not to enforce any such threat to convert them into fire worship, since their conviction was final and firm. The Battle of Avarair was inevitable. On the battlefield the Armenian army, far smaller than the Persian army, headed by General Vartan and Priest Ghevond fought against the enemy, fell and gave their lives as our martyrs and witnesses of Christ, but eventually in 484 were given their right to worship Christ by signing the Treaty of Nevarsak. This was the first war ever in history waged in defense of Christianity.

It is important to learn the following lesson from history. While Armenia was successfully determined to resist and keep her language and religion up to this day, Persia not too long after the Battle of Avarair, abandoned Zoroastrianism and embraced Islam. Iran further changed its language from the Bahlav to the Persian, and abandoned their scripts and adopted the Arabic letters. The Armenians stood victorious to the last.

Religious unrest in Armenia in that same year 451 was strongly felt as a reaction from the West, this time under the continued pressures of the Byzantine Empire, under the pretext of Christological issues, aiming at religious subjugation of the Armenian Church to the Byzantine Church. The former ignored and eventually rejected to consider any such demand, insisting on the final declaration of the Christological issue reached at the Council of Ephesus in 381. It was in 506, under Catholicos Babken I of Othmus, when the rejection of the Council of Chalcedon of 451 AD and its resolutions became final, and no further problems of subjection were seriously considered by the Armenian Church.

Patristic Literature

Soon after the invention of the Armenian alphabet and the translation of the Bible into Armenian, literary activities bloomed in Armenia as the most urgent need for the formation of Armenian Christianity from its foundations. Patristic works of Greek and Syrian Fathers of the Church included liturgical texts as well as commentaries of the Bible. Armenian translators embarked on this task and began to read and translate the Chronicle of Eusebius of Caesarea (c.260-c.340), his second book after the famous Ecclesiastical History, which was lost but the Armenian version had survived and was found centuries later, at the beginning of the 19th century, which served as the «original» of the Chronicle. It was the last resort for the restoration of that particular text.

Works of Bishop Irenaeus of Lyons (c.130-c.200), which included Against the Heresies, were also translated into Armenian in the fifth century. It proved to be very important since some of Irenaeus» original texts were lost and the Armenian translations were indispensable, such was The Demonstration of the Apostolic Preaching, which was discovered in an Armenian translation in 1907 by an Armenian cleric scholar in Etchmiadzin, who translated it into German, and later into Latin in 1917, and into other languages. The point we are making is not as much to demonstrate the availability of ancient and rare translation of certain texts, but to ascertain the earliest sources and foundations on which the Armenian Church was established through literary activities by genuine translations.

The above facts demonstrate that the 3rd and 4th centuries marked major spiritual growth of the Church by way of worship which required texts for liturgy and daily services. The emergence of liturgical texts was an integral and permanent part of the worship which the Armenian Translators, the immediate disciples of Sahag and Mesrob, took upon themselves as their primary task. Now eloquent in Greek and Syriac languages, they lost no time in gathering and reading the existing liturgical texts extensively, especially the Liturgies of St. Athanasius, St. Basil of Caesarea, and St. John Chrysostom, for the proper use of the Armenian Church worship.

During the fifth century, Armenia was also enriched by literature other than purely liturgical and devotional which contributed greatly to the formation of the Armenian Apostolic Church. One of them was the Epic of Yeghishe Vardapet, known as Concerning Vartan and the War of the Armenians, which was an eye-witness account of the 451 Battle of Avarair, written in a pure classical language and poetry. There was also the Refutation of the Sects by Eznik Goghpatsi, a most valuable exposition of philosophical evaluation of God’s existence by way of refuting the existing sects of the time, including Mazdeism of Persia, ancient Greek philosophies, and the sect of Marcion. His central thesis has been to defend the existence of God through the revelation of Christianity.

Eznik’s classic work is unique in the ancient literature of the Armenian people with its most superb classic Armenian, shaped on the language of the Armenian Bible, translated partially by himself as one of the first disciples of Mesrob. His treatise contains numerous biblical citations, having in mind God’s existence as against the false doctrines of his time, such as the Manichaeism, founded by Mani and known at the time as a syncretic mixture of Christianity and Iranian belief, powerful enough to merge the two rival thoughts, Christian and Iranian, into a higher synthesis. Eznik also refuted the ancient Greek Pythagorean, Epicurean, and Stoic philosophies in defense of Christianity by way of reconciling it with the more moderate and God-centered philosophies of Plato and Aristotle.

Thus, under the shadow of the Armenian Bible sources flourished and further reinforced the formation and built the identity of the Armenian Church. Since we are confined within the fifth century alone, other written sources and historiographies no doubt contributed to the stability of the Armenian Church in the subsequent centuries. There is one ascribed to St. Gregory the Illuminator, known as Hajaghapatum Jark, a collection of theological and religious-ethical sermons, and another is History of the Armenians by Movses Khorenatsi, the most famous fifth century historian, who has combined pre-historic Armenia with the events of his own days as a continuous existence of Armenia and the Armenians. His work has served as the magnum opus for the next historians up to the 18th century. The History of Agathangelos, the History of Bavstos Buzand, the History of Ghazar Barpetsi, and later the History of Bishop Sebeos, have added one way or another to the formation of the Armenian Church.

Even though not finalized during the centuries under consideration, the Armenian Church Sharagans, the Hymns, had their origin in the fifth century, even some of them authored by St. Sahag and St. Mesrob. They contained variety of hymns related to the fundamental theological and national issues, all of them eventually forming an impressive collection of songs with their proper music. They also undoubtedly contributed considerably to the formation of the Armenian Church as an authentic church for the Armenian people exclusively.

Lastly, the Canon Law of the Armenian Church drew the line and controlled the discipline of this church as an established institution, beginning from the fifth century but culminating into a final compilation as a code in the eighth century by a famous Catholicos John of Otsoon (717-728), famed as the «philosopher» pontiff of the Armenian Church. He compiled the laws adopted by previously convened Armenian Church Councils, «classified and finalized them chronologically and installed them permanently in his pontifical office», as stated by the Catholicos. He too convened a Church Council of Manazkert in 726 and established new canons concerning the person of Christ.

During the pontificate of Catholicos Vasken I (1955-1994), the Canon Law as compiled by John of Otsoon was once and for all published in two volumes in Erevan, in 1964 and 1971, by Vazken Hakopian, a specialist in the field of canon law, after minute examinations of the different readings of 47 manuscript texts of the original Canon Law, copied throughout the centuries following the original compilation. Hakopian classified the laws under 57 groups, with a total number of 1332 individual canon laws. For example, the Council of Shahapivan in 444 adopted 20 canons purely under political circumstances, when in 428 the Armenian kingdom of the Arshakuni dynasty fell, and Armenian princes fell in quarrels with each other. It is interesting to note that the laws of Shahapivan were formulated and enforced by a church council to judge political leaders of Armenia in time of crises. Also, the Armenian Church Council of Dvin in 648, presided by Catholicos Nersess III with 17 bishops participating, adopted 12 canons to resist the invasions of the Arabs in defense of the Armenian princes. The Council set rules to resist the Byzantine pressure.

RETURN OF THE PONTIFICAL

MOTHER SEE FROM SIS TO ETCHMIADZIN

(1292-1441)

The National-Ecclesiastical

Assembly (1945)

Archbishop Kevork Chorekjian, the locum tenens of the Mother See convened the delayed National-Ecclesiastical Assembly in June 1945, after a long period of vacancy following the tragic death of Catholicos Khoren I Mouradbekian, who was found strangled in 1938 in his patriarchal residence by the chief Armenian Bolsheviks for not handing over the keys to the treasures of the Holy See. The locum tenens of the Holy See had hard time to convene the Assembly for the election of the next Catholicos for seven years due to the harsh regime. Finally the Assembly took place in 1945 presided over by Catholicos of Cilicia Karekin I Hovsepiants and in the attendance of several bishops and lay delegates from Armenia and abroad. They elected Archbishop Kevork Chorekjian as KEVORK VI Catholicos of All Armenians.

The consecration of the Catholicos took place by His Holiness Catholicos Karekin I of the Great House of Cilicia who traveled from Antelias, Lebanon, accompanied by two archbishops and lay delegates. At the ordination of Kevork VI, the Catholicos of Cilicia was assisted by six archbishops: Kevork Arslanian (Istanbul), Garabed Mazlumian (Greece), Yeprem Dohmuni (Damascus), Ardavast Surmeyian (Aleppo), Mampre Sirounian (Egypt), and Mampre Kalfayan (United States), all of them from abroad, “indicating” there was not a single bishop left in Holy Etchmiadzin. That was extremely alarming. Ten new bishops were ordained by the new Catholicos immediately after the consecration of Catholicos Kevork VI, half of them from abroad.

The Special Agenda

The lengthy agenda of the Assembly included the 570th anniversary of the Return of the Mother See of the Catholicos of All Armenians from Sis, Cilicia in 1441, where it stayed from 1292. Given the political situations, the Patriarchal See temporarily transferred at first to Dvin, Aghtamar, Ani, Argina, Hromkla and finally to Sis, in total of 950 years. The final return to its original site Holy Etchmiadzin (Vagharshapat) as an important remembrance was discussed and a resolution passed on its June 19th session by the National-Ecclesiastical Assembly to commemorate the event annually, each year on Thursday, on the feast of the Ascension of Christ, declaring the year 1945-1946 as “The year of Return of the Pontifical See to Holy Etchmiadzin”. The return in 1441 was also on Ascension Thursday.

The First Encyclical

The newly-elected Catholicos Kevork VI of All Armenians dispatched his First Encyclical dated April 1, 1946, mentioning the various places the Holy See had transferred for centuries, and finally returned to its original site. The Catholicos specified “the year 1292 as the year the Holy See was transferred to Sis, the capital of the Rubenian (Cilician) Kingdom, where it remained for 149 years.” The Catholicos described the last station of the Holy See as “disastrous,” since there was no political stability after the fall of the Cilician Kingdom in 1375. The final return was the only way to safeguard the Pontificate’s existence and spiritual leadership worldwide.

There was however the problem of the last Catholicos of All Armenians Krikor Musabekian, who was invited to return with the Holy See and preside over the Assembly of 1441 in Vagharshapat. His return would have been the natural transfer of the See, with no reason for a new election, but because he declined, and at the same time did not object the Assembly to convene, the Assembly in Etchmiadzin took place as scheduled. Krikor stayed in Sis to safeguard the local Holy See in Cilicia. Unfortunately the Return of the Patriarchal See experienced division between the two Sees. The Assembly, with some 400 religious and lay delegates, elected a new Catholicos, Kirakos of Khorvirap, who was installed as KIRAKOS I of All Armenians. The relation between the two, however, was divided but cordial, though at times hostile, but after the transfer and the election of his successor, Catholicos Krikor Musabekian recognized the supremacy of Holy Etchmiadzin, and the Mother See in turn recognized the Cilician See as “limited and partial” (masnavor), exclusively for Cilicia.

The Eastern Vardapets (Doctors)

Behind the historic return of the Holy See stood a group of educated and dedicated Eastern Vardapets (Doctors of the Armenian Church), who were keeping alive the numerous monasteries and the universities and supervising the teaching and the discipline of those schools. Such were, the Monasteries of Datev, Glatzor and Noravank in Siunik, Haghbat and Sanahin in north Armenia, the monastery of Geghart and Haghardzin, and others, all of them centers of higher education. Highly respectable educators, such as leading clerics Yesai Nchetsi, Nersess Mshetsi, Hovhan Vorotnetsi, Krikor Datevatsi, Kirakos Gandzaketsi, Vartan Areveltsi, just to name a few, were in the lead for the return of the Holy See, despite politically unstable years in Armenia under the Persian Khans.

The Celebrations

Catholicos Kevork VI had directed all Armenian dioceses and churches to celebrate the historic event with elaborate religious and cultural programs. The first among them was Giuregh II, the Armenian Patriarch of Jerusalem who had attended the 1945 Assembly as the elected and installed Patriarch and had been ordained bishop by the new Catholicos Kevork VI, heading the group of ten candidates. The Catholicos had also bestowed on him the rank of Archbishop. Patriarch Archbishop Giuregh II wrote a lengthy article in the official monthly SION, reflecting on the Encyclical, the history of the Holy See, and finally on its return, which, he said, marked a great milestone in our church history. He found the See’s wandering in different locations forcefully applied, and for the longest time, brought a serious danger on its revival. “The return was once and for all truly providential,” as the Patriarch wrote. Annually, on Ascension Thursday the Armenian Church offers a special service following the Divine Liturgy known as “hayrapetakan maghtank”, a Pontifical Thanksgiving Service, in commemoration of the final return of the Pontifical See of All Armenians to its original site Holy Etchmiadzin.

SEAL OF FAITH” – “KNIK HAVADO”

A 7th Century Theological Collection

Compiled by

Catholicos Komitas I of Armenia

(615-628)

The Manuscript

In 1911 Bishop Karapet Ter Mkrtchyan of Holy Etchmiadzin, a renowned scholar, studied in Germany and upon his return while teaching at the Seminary and holding the office of primate under the Mother See, discovered this unique collection of the Armenian Manuscript in the Armenian Church of St. Stepanos Nakhavka (Proto-martyr) in Darashamb, northern Iran, in the province of Maku. Darashamb had 280 Armenian populations until 1916. It was a historic discovery, since the collection contained the “Seal of Faith” (Knik Havado) in its entirety compiled by Catholicos Komitas Aghtsetsi (615-628). Independently this document has its twin brother, as important, known as the “Book of Letters” (Girk Tghtots), both of them mentioned by Armenian historians as documents supporting the orthodox doctrine of the Armenian Church. Both were lost for many centuries. Thanks to Bishop Ter Mkrtchyan, who persistently looked for the Seal of Faith and found it in the large manuscript collection kept in the Armenian Church in Iran. The Bishop, after careful study, published the textwith ample annotations and an in-depth Introduction in 1914.

As for the “Book of Letters,” it is a collection of letters also originally compiled by Komitas Catholicos, but later in the succeeding centuries more letters were added and made in total 98 letters. It contains letters of doctrine based on the first Three Ecumenical Councils, from the 5th to the 13th centuries. The opening of the “Book of Letters” shows a 5th c. letter by the Greek Orthodox Patriarch Proglus of Alexandria addressed to the Armenian Catholicos St. Sahak Parthev, condemning Nestorius and his heresy which was penetrating into Armenia. The Armenian Church then, just having invented its national scripts and translated the Bible into Armenian for the first time by St. Sahak and St. Mesrop, had to defend its independence, free from further doctrines added since the days of St. Gregory the Illuminator.

Another significant work also was accomplished by Bishop Ter Mkrtchyan and his colleague, a well known scholar Yervant Ter Minassian, who together discovered and later published the German translation of St. Irenaeus, Bishop of Lyons’ (130-200) “The Demonstration of the Apostolic Preaching,” whose Greek original was lost and the classical Armenian translation had survived. A year later both scholars published yet another ancient source, the work of Timothy Aelurus, the monophysite Patriarch of Alexandria (457-477), known as “A Collection of Treatises and Letters Against the Council of Chalcedon,” in both Armenian (“Hakajarrutyunk”) and German versions.

Ter Mkrtchyan was ordained celibate priest by the orders of Catholicos Mkrtich Khrimian of All Armenians in 1894, and served briefly as Vicar of the Ararat Diocese (1903-1905) showing brave resistance against the Russians demands and interference to confiscate the Armenian schools in Armenia. Later in 1909 he was ordained bishop by Catholicos Matthew II Izmirlian, holding successively the office of primate in the dioceses of Astrakhan and Shamakh until 1914.

The Content

The“Seal of Faith,” as published, contains 10 chapters referring to the various doctrinal issues in each, such as, the Holy Trinity, the Incarnation of Christ, the Immaculate Birth of Jesus, the relation between Christ’s two natures, all supported by some 50 ancient divines. Some are mentioned by name, as Sts. Gregory the Illuminator, Sahak Parthev Catholicos, Mesrop Mashtots the creator of the Armenian letters, Eznik Koghbatsi bishop of Bagrevand, who was the first erudite apologist of Christianity, along with historians Agathangelos, John Catholicos Mandakuni, as well as Syrian theologian Ephraem, John Chrysostom, and the three Cappadocian Fathers, Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nyssa, and Gregory of Nazianzus.

The Seal of Faith reflects the teachings of “The orthodox doctrine professed by our forefathers,” as the publisher specifies, pointing to the anti-Chalcedonian stand of the Armenian Church which never followed nor agreed to the Christological doctrine of the Council of Chalcedon of 451, despite persistent pressures by the Byzantines. Eventually, a few decades after Chalcedon, the Armenian Church officially rejected the doctrine and its endorsement by the “Tome of Pope Leo.” The decision was officially adopted at the Armenian Church Council of Dvin in 506, presided by the Armenian Catholicos Babken I of Othmus, who entered the resolution in the Canon Book once and for all.

Bishop Ter Mkrtchyan has made the following remarks: “This book was essential as written evidence in case it became necessary to refute the wrong teachings of the heretics.” The Armenian Church is forever grateful to Bishop Karapet, the brilliant scholar who published the Seal of Faith in 1914 in Holy Etchmiadzin and which remains as the oldest verifiable source of our theology, by date and by author.

Catholicos Komitas I Aghtsetsi

The Council of Persia in 614

Bishop Ter Mkrtchyan verifies that this theological document was essentially the report Bishop Komitas of the Mamikonian dynasty, read at the Council of 614 in Ctesiphon, capital of Sassanid Persia, convened and presided over by the Persian King Khosrov II Parvez (590-628). According to the Armenian historians Sebeos (7th c.), and Stepanos Asoghik Taronetsi (10th c.), the king had called the Council at his “royal court” to reach agreement among his Christian subjects who disputed among themselves in matters of faith and ended up in schisms.

Addressing the attending bishops at the Council, Bishop Komitas said: “Ask for the Christ-loving faith of the Armenians as you have come here at the royal court,” meaning that the bishops had come to learn about the faith of the Armenian Church. The focal question was always on the doctrine of the Person of Christ and his two natures, divine and human. Komitas was defending the doctrine reached and proclaimed during the first Three Ecumenical Councils, especially the third Council of Ephesus in 431, where the dominant theologian was Cyril, Patriarch of Alexandria, whose formula was final and accepted by all attending church representatives: “One Nature of the Incarnate Word.”

Beside Bishop Komitas, who soon became the Catholicos of Armenia, Bishop Matthew Amatouni, and the exiled Patriarch Zechariah of Jerusalem were among the bishops. The first two were representing the Armenian princes and clergy “so that they could receive the proper protection and the confirmation of their faith by the King of Persia.” The signed document at the Persian Council of 614 stated: “Komitas, Bishop of the Mamikonians, who succeeded as Catholicos of Greater Armenia.” Scholars further believe that later two venerable clerics have compiled this work after Komitas, namely Hovhannes Mayragometsi (7th c.), the author of “Havatarmat” (The Root of Faith), and the famous theologian Stepanos Siunetsi (8th c.).

At the Council called by the king of Persia in 614 Komitas read “a lengthy” paper which our church historian Patriarch Malachia Ormanian considers “complete enough” to warrant the compilation of the “Seal of Faith” by the same Bishop, now Catholicos of All Armenians. Ormanian had not read the book when completing the first volume of his “Azgapatum,” (History of the Nation), since the “Seal of Faith” was not published as yet. To that effect, Bishop Ter Mkrtchyan states in the Introduction that “The basic part of the Seal of Faith stemmed from the lengthy paper he [Komitas] read at the Council on behalf of the faith and doctrine of the Armenian Church.” Ormanian’s additional remark is also important: “Catholicos Komitas began exercising his patriarchal authority even while in Persia, where at the Council he presented his lengthy paper concerning the Armenian faith”. He believes that the paper was a defense of the doctrine and the rejection of most of the heresies of which 25 are specified by name. Ormanian says that controversial bishops were also attending the Council, nine of them reported by name.

It is important what our historians say about the final document. It was handed to King Khosrov Parvez, signed by the 11 attending bishops whose names are likewise reported by them. The King soon consulted Patriarch Zechariah of Jerusalem, asking him where the truth lied regarding Christ’s identity, to which the Patriarch answered: “The truth of our faith lies in what we learn at the Council of Nicaea, called then by the blessed Constantine, and later at the Councils of Constantinople and Ephesus, where the Armenians united in the true faith. As for the Council of Chalcedon, its doctrine was not in unison with the previous Councils, as it was explained to Your Majesty.”

The King reached the following conclusion: “All those Christians who are my subjects shall hold the faith that the Armenians adhere to. He also ordered to seal with his ring the paper of the correct faith and deposit it in the royal archives.” (Cf. Sebeos, History of Heraclius, chapter 46. Ed. Kevork Abgaryan, Yerevan, 1979).

The Legacy of Komitas Catholicos

Beside the “Seal of Faith” and “The Book of Letters,” Catholicos Komitas has left two authentic and supreme legacies: The Church of St. Hripsimeh in Etchmiadzin, built by him in 618, which up to this date stands miraculously as the most authentic and unique sample of the Armenian Church architecture, and the Hymn known as “Antzink nviryalk sirooyn Krisdosi,” (Souls dedicated to the love of Christ), written by him in 36 stanzas according to the alphabet of the Armenian language, dedicated to the memory of the Roman Virgins Hripsimyank and Gayanyank and their companions, who were the first martyrs to witness Christ after being persecuted by the Roman Emperor, and upon arrival to Armenia were martyred by King Trdat III Arshakuni (298-330), by the orders of the Emperor. The hymn is the oldest verifiable hymn by author and date in the entire Hymnbook of the Armenian Church, a volume which was gradually compiled and completed in the span of 1000 years, from the 5th to the 15th centuries.

The Armenian Church and nation is forever grateful to Catholicos Komitas and Bishop Karapet Ter Mkrtchyan for the three-fold legacy beyond any reservation: The Seal of Faith, the Church of St. Hripsimeh, and the Hymn dedicated to their memories. In recent years a musicologist Krikor Pidedgian wrote an important book on the Hymn giving an in-depth and complete analysis of the 36 stanzas historically and from the musical point of view. Pidedgian has made an educated comparison with similar hymns that are composed on the same musical mode, after the style of the Armenian Church music.

SEAL OF FAITH” – “KNIK HAVADO”

A 7th Century Theological Collection

Compiled by

Catholicos Komitas I of Armenia

(615-628)

The Manuscript

In 1911 Bishop Karapet Ter Mkrtchyan of Holy Etchmiadzin, a renowned scholar, studied in Germany and upon his return while teaching at the Seminary and holding the office of primate under the Mother See, discovered this unique collection of the Armenian Manuscript in the Armenian Church of St. Stepanos Nakhavka (Proto-martyr) in Darashamb, northern Iran, in the province of Maku. Darashamb had 280 Armenian populations until 1916. It was a historic discovery, since the collection contained the “Seal of Faith” (Knik Havado) in its entirety compiled by Catholicos Komitas Aghtsetsi (615-628). Independently this document has its twin brother, as important, known as the “Book of Letters” (Girk Tghtots), both of them mentioned by Armenian historians as documents supporting the orthodox doctrine of the Armenian Church. Both were lost for many centuries. Thanks to Bishop Ter Mkrtchyan, who persistently looked for the Seal of Faith and found it in the large manuscript collection kept in the Armenian Church in Iran. The Bishop, after careful study, published the textwith ample annotations and an in-depth Introduction in 1914.

As for the “Book of Letters,” it is a collection of letters also originally compiled by Komitas Catholicos, but later in the succeeding centuries more letters were added and made in total 98 letters. It contains letters of doctrine based on the first Three Ecumenical Councils, from the 5th to the 13th centuries. The opening of the “Book of Letters” shows a 5th c. letter by the Greek Orthodox Patriarch Proglus of Alexandria addressed to the Armenian Catholicos St. Sahak Parthev, condemning Nestorius and his heresy which was penetrating into Armenia. The Armenian Church then, just having invented its national scripts and translated the Bible into Armenian for the first time by St. Sahak and St. Mesrop, had to defend its independence, free from further doctrines added since the days of St. Gregory the Illuminator.

Another significant work also was accomplished by Bishop Ter Mkrtchyan and his colleague, a well known scholar Yervant Ter Minassian, who together discovered and later published the German translation of St. Irenaeus, Bishop of Lyons’ (130-200) “The Demonstration of the Apostolic Preaching,” whose Greek original was lost and the classical Armenian translation had survived. A year later both scholars published yet another ancient source, the work of Timothy Aelurus, the monophysite Patriarch of Alexandria (457-477), known as “A Collection of Treatises and Letters Against the Council of Chalcedon,” in both Armenian (“Hakajarrutyunk”) and German versions.

Ter Mkrtchyan was ordained celibate priest by the orders of Catholicos Mkrtich Khrimian of All Armenians in 1894, and served briefly as Vicar of the Ararat Diocese (1903-1905) showing brave resistance against the Russians demands and interference to confiscate the Armenian schools in Armenia. Later in 1909 he was ordained bishop by Catholicos Matthew II Izmirlian, holding successively the office of primate in the dioceses of Astrakhan and Shamakh until 1914.

The Content

The“Seal of Faith,” as published, contains 10 chapters referring to the various doctrinal issues in each, such as, the Holy Trinity, the Incarnation of Christ, the Immaculate Birth of Jesus, the relation between Christ’s two natures, all supported by some 50 ancient divines. Some are mentioned by name, as Sts. Gregory the Illuminator, Sahak Parthev Catholicos, Mesrop Mashtots the creator of the Armenian letters, Eznik Koghbatsi bishop of Bagrevand, who was the first erudite apologist of Christianity, along with historians Agathangelos, John Catholicos Mandakuni, as well as Syrian theologian Ephraem, John Chrysostom, and the three Cappadocian Fathers, Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nyssa, and Gregory of Nazianzus.

The Seal of Faith reflects the teachings of “The orthodox doctrine professed by our forefathers,” as the publisher specifies, pointing to the anti-Chalcedonian stand of the Armenian Church which never followed nor agreed to the Christological doctrine of the Council of Chalcedon of 451, despite persistent pressures by the Byzantines. Eventually, a few decades after Chalcedon, the Armenian Church officially rejected the doctrine and its endorsement by the “Tome of Pope Leo.” The decision was officially adopted at the Armenian Church Council of Dvin in 506, presided by the Armenian Catholicos Babken I of Othmus, who entered the resolution in the Canon Book once and for all.

Bishop Ter Mkrtchyan has made the following remarks: “This book was essential as written evidence in case it became necessary to refute the wrong teachings of the heretics.” The Armenian Church is forever grateful to Bishop Karapet, the brilliant scholar who published the Seal of Faith in 1914 in Holy Etchmiadzin and which remains as the oldest verifiable source of our theology, by date and by author.

Catholicos Komitas I Aghtsetsi

The Council of Persia in 614

Bishop Ter Mkrtchyan verifies that this theological document was essentially the report Bishop Komitas of the Mamikonian dynasty, read at the Council of 614 in Ctesiphon, capital of Sassanid Persia, convened and presided over by the Persian King Khosrov II Parvez (590-628). According to the Armenian historians Sebeos (7th c.), and Stepanos Asoghik Taronetsi (10th c.), the king had called the Council at his “royal court” to reach agreement among his Christian subjects who disputed among themselves in matters of faith and ended up in schisms.

Addressing the attending bishops at the Council, Bishop Komitas said: “Ask for the Christ-loving faith of the Armenians as you have come here at the royal court,” meaning that the bishops had come to learn about the faith of the Armenian Church. The focal question was always on the doctrine of the Person of Christ and his two natures, divine and human. Komitas was defending the doctrine reached and proclaimed during the first Three Ecumenical Councils, especially the third Council of Ephesus in 431, where the dominant theologian was Cyril, Patriarch of Alexandria, whose formula was final and accepted by all attending church representatives: “One Nature of the Incarnate Word.”

Beside Bishop Komitas, who soon became the Catholicos of Armenia, Bishop Matthew Amatouni, and the exiled Patriarch Zechariah of Jerusalem were among the bishops. The first two were representing the Armenian princes and clergy “so that they could receive the proper protection and the confirmation of their faith by the King of Persia.” The signed document at the Persian Council of 614 stated: “Komitas, Bishop of the Mamikonians, who succeeded as Catholicos of Greater Armenia.” Scholars further believe that later two venerable clerics have compiled this work after Komitas, namely Hovhannes Mayragometsi (7th c.), the author of “Havatarmat” (The Root of Faith), and the famous theologian Stepanos Siunetsi (8th c.).

At the Council called by the king of Persia in 614 Komitas read “a lengthy” paper which our church historian Patriarch Malachia Ormanian considers “complete enough” to warrant the compilation of the “Seal of Faith” by the same Bishop, now Catholicos of All Armenians. Ormanian had not read the book when completing the first volume of his “Azgapatum,” (History of the Nation), since the “Seal of Faith” was not published as yet. To that effect, Bishop Ter Mkrtchyan states in the Introduction that “The basic part of the Seal of Faith stemmed from the lengthy paper he [Komitas] read at the Council on behalf of the faith and doctrine of the Armenian Church.” Ormanian’s additional remark is also important: “Catholicos Komitas began exercising his patriarchal authority even while in Persia, where at the Council he presented his lengthy paper concerning the Armenian faith”. He believes that the paper was a defense of the doctrine and the rejection of most of the heresies of which 25 are specified by name. Ormanian says that controversial bishops were also attending the Council, nine of them reported by name.

It is important what our historians say about the final document. It was handed to King Khosrov Parvez, signed by the 11 attending bishops whose names are likewise reported by them. The King soon consulted Patriarch Zechariah of Jerusalem, asking him where the truth lied regarding Christ’s identity, to which the Patriarch answered: “The truth of our faith lies in what we learn at the Council of Nicaea, called then by the blessed Constantine, and later at the Councils of Constantinople and Ephesus, where the Armenians united in the true faith. As for the Council of Chalcedon, its doctrine was not in unison with the previous Councils, as it was explained to Your Majesty.”

The King reached the following conclusion: “All those Christians who are my subjects shall hold the faith that the Armenians adhere to. He also ordered to seal with his ring the paper of the correct faith and deposit it in the royal archives.” (Cf. Sebeos, History of Heraclius, chapter 46. Ed. Kevork Abgaryan, Yerevan, 1979).

The Legacy of Komitas Catholicos

Beside the “Seal of Faith” and “The Book of Letters,” Catholicos Komitas has left two authentic and supreme legacies: The Church of St. Hripsimeh in Etchmiadzin, built by him in 618, which up to this date stands miraculously as the most authentic and unique sample of the Armenian Church architecture, and the Hymn known as “Antzink nviryalk sirooyn Krisdosi,” (Souls dedicated to the love of Christ), written by him in 36 stanzas according to the alphabet of the Armenian language, dedicated to the memory of the Roman Virgins Hripsimyank and Gayanyank and their companions, who were the first martyrs to witness Christ after being persecuted by the Roman Emperor, and upon arrival to Armenia were martyred by King Trdat III Arshakuni (298-330), by the orders of the Emperor. The hymn is the oldest verifiable hymn by author and date in the entire Hymnbook of the Armenian Church, a volume which was gradually compiled and completed in the span of 1000 years, from the 5th to the 15th centuries.

The Armenian Church and nation is forever grateful to Catholicos Komitas and Bishop Karapet Ter Mkrtchyan for the three-fold legacy beyond any reservation: The Seal of Faith, the Church of St. Hripsimeh, and the Hymn dedicated to their memories. In recent years a musicologist Krikor Pidedgian wrote an important book on the Hymn giving an in-depth and complete analysis of the 36 stanzas historically and from the musical point of view. Pidedgian has made an educated comparison with similar hymns that are composed on the same musical mode, after the style of the Armenian Church music.

SEAL OF FAITH” – “KNIK HAVADO”

A 7th Century Theological Collection

Compiled by

Catholicos Komitas I of Armenia

(615-628)

The Manuscript

In 1911 Bishop Karapet Ter Mkrtchyan of Holy Etchmiadzin, a renowned scholar, studied in Germany and upon his return while teaching at the Seminary and holding the office of primate under the Mother See, discovered this unique collection of the Armenian Manuscript in the Armenian Church of St. Stepanos Nakhavka (Proto-martyr) in Darashamb, northern Iran, in the province of Maku. Darashamb had 280 Armenian populations until 1916. It was a historic discovery, since the collection contained the “Seal of Faith” (Knik Havado) in its entirety compiled by Catholicos Komitas Aghtsetsi (615-628). Independently this document has its twin brother, as important, known as the “Book of Letters” (Girk Tghtots), both of them mentioned by Armenian historians as documents supporting the orthodox doctrine of the Armenian Church. Both were lost for many centuries. Thanks to Bishop Ter Mkrtchyan, who persistently looked for the Seal of Faith and found it in the large manuscript collection kept in the Armenian Church in Iran. The Bishop, after careful study, published the textwith ample annotations and an in-depth Introduction in 1914.

As for the “Book of Letters,” it is a collection of letters also originally compiled by Komitas Catholicos, but later in the succeeding centuries more letters were added and made in total 98 letters. It contains letters of doctrine based on the first Three Ecumenical Councils, from the 5th to the 13th centuries. The opening of the “Book of Letters” shows a 5th c. letter by the Greek Orthodox Patriarch Proglus of Alexandria addressed to the Armenian Catholicos St. Sahak Parthev, condemning Nestorius and his heresy which was penetrating into Armenia. The Armenian Church then, just having invented its national scripts and translated the Bible into Armenian for the first time by St. Sahak and St. Mesrop, had to defend its independence, free from further doctrines added since the days of St. Gregory the Illuminator.

Another significant work also was accomplished by Bishop Ter Mkrtchyan and his colleague, a well known scholar Yervant Ter Minassian, who together discovered and later published the German translation of St. Irenaeus, Bishop of Lyons’ (130-200) “The Demonstration of the Apostolic Preaching,” whose Greek original was lost and the classical Armenian translation had survived. A year later both scholars published yet another ancient source, the work of Timothy Aelurus, the monophysite Patriarch of Alexandria (457-477), known as “A Collection of Treatises and Letters Against the Council of Chalcedon,” in both Armenian (“Hakajarrutyunk”) and German versions.

Ter Mkrtchyan was ordained celibate priest by the orders of Catholicos Mkrtich Khrimian of All Armenians in 1894, and served briefly as Vicar of the Ararat Diocese (1903-1905) showing brave resistance against the Russians demands and interference to confiscate the Armenian schools in Armenia. Later in 1909 he was ordained bishop by Catholicos Matthew II Izmirlian, holding successively the office of primate in the dioceses of Astrakhan and Shamakh until 1914.

The Content

The“Seal of Faith,” as published, contains 10 chapters referring to the various doctrinal issues in each, such as, the Holy Trinity, the Incarnation of Christ, the Immaculate Birth of Jesus, the relation between Christ’s two natures, all supported by some 50 ancient divines. Some are mentioned by name, as Sts. Gregory the Illuminator, Sahak Parthev Catholicos, Mesrop Mashtots the creator of the Armenian letters, Eznik Koghbatsi bishop of Bagrevand, who was the first erudite apologist of Christianity, along with historians Agathangelos, John Catholicos Mandakuni, as well as Syrian theologian Ephraem, John Chrysostom, and the three Cappadocian Fathers, Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nyssa, and Gregory of Nazianzus.

The Seal of Faith reflects the teachings of “The orthodox doctrine professed by our forefathers,” as the publisher specifies, pointing to the anti-Chalcedonian stand of the Armenian Church which never followed nor agreed to the Christological doctrine of the Council of Chalcedon of 451, despite persistent pressures by the Byzantines. Eventually, a few decades after Chalcedon, the Armenian Church officially rejected the doctrine and its endorsement by the “Tome of Pope Leo.” The decision was officially adopted at the Armenian Church Council of Dvin in 506, presided by the Armenian Catholicos Babken I of Othmus, who entered the resolution in the Canon Book once and for all.

Bishop Ter Mkrtchyan has made the following remarks: “This book was essential as written evidence in case it became necessary to refute the wrong teachings of the heretics.” The Armenian Church is forever grateful to Bishop Karapet, the brilliant scholar who published the Seal of Faith in 1914 in Holy Etchmiadzin and which remains as the oldest verifiable source of our theology, by date and by author.

Catholicos Komitas I Aghtsetsi

The Council of Persia in 614

Bishop Ter Mkrtchyan verifies that this theological document was essentially the report Bishop Komitas of the Mamikonian dynasty, read at the Council of 614 in Ctesiphon, capital of Sassanid Persia, convened and presided over by the Persian King Khosrov II Parvez (590-628). According to the Armenian historians Sebeos (7th c.), and Stepanos Asoghik Taronetsi (10th c.), the king had called the Council at his “royal court” to reach agreement among his Christian subjects who disputed among themselves in matters of faith and ended up in schisms.

Addressing the attending bishops at the Council, Bishop Komitas said: “Ask for the Christ-loving faith of the Armenians as you have come here at the royal court,” meaning that the bishops had come to learn about the faith of the Armenian Church. The focal question was always on the doctrine of the Person of Christ and his two natures, divine and human. Komitas was defending the doctrine reached and proclaimed during the first Three Ecumenical Councils, especially the third Council of Ephesus in 431, where the dominant theologian was Cyril, Patriarch of Alexandria, whose formula was final and accepted by all attending church representatives: “One Nature of the Incarnate Word.”

Beside Bishop Komitas, who soon became the Catholicos of Armenia, Bishop Matthew Amatouni, and the exiled Patriarch Zechariah of Jerusalem were among the bishops. The first two were representing the Armenian princes and clergy “so that they could receive the proper protection and the confirmation of their faith by the King of Persia.” The signed document at the Persian Council of 614 stated: “Komitas, Bishop of the Mamikonians, who succeeded as Catholicos of Greater Armenia.” Scholars further believe that later two venerable clerics have compiled this work after Komitas, namely Hovhannes Mayragometsi (7th c.), the author of “Havatarmat” (The Root of Faith), and the famous theologian Stepanos Siunetsi (8th c.).

At the Council called by the king of Persia in 614 Komitas read “a lengthy” paper which our church historian Patriarch Malachia Ormanian considers “complete enough” to warrant the compilation of the “Seal of Faith” by the same Bishop, now Catholicos of All Armenians. Ormanian had not read the book when completing the first volume of his “Azgapatum,” (History of the Nation), since the “Seal of Faith” was not published as yet. To that effect, Bishop Ter Mkrtchyan states in the Introduction that “The basic part of the Seal of Faith stemmed from the lengthy paper he [Komitas] read at the Council on behalf of the faith and doctrine of the Armenian Church.” Ormanian’s additional remark is also important: “Catholicos Komitas began exercising his patriarchal authority even while in Persia, where at the Council he presented his lengthy paper concerning the Armenian faith”. He believes that the paper was a defense of the doctrine and the rejection of most of the heresies of which 25 are specified by name. Ormanian says that controversial bishops were also attending the Council, nine of them reported by name.

It is important what our historians say about the final document. It was handed to King Khosrov Parvez, signed by the 11 attending bishops whose names are likewise reported by them. The King soon consulted Patriarch Zechariah of Jerusalem, asking him where the truth lied regarding Christ’s identity, to which the Patriarch answered: “The truth of our faith lies in what we learn at the Council of Nicaea, called then by the blessed Constantine, and later at the Councils of Constantinople and Ephesus, where the Armenians united in the true faith. As for the Council of Chalcedon, its doctrine was not in unison with the previous Councils, as it was explained to Your Majesty.”

The King reached the following conclusion: “All those Christians who are my subjects shall hold the faith that the Armenians adhere to. He also ordered to seal with his ring the paper of the correct faith and deposit it in the royal archives.” (Cf. Sebeos, History of Heraclius, chapter 46. Ed. Kevork Abgaryan, Yerevan, 1979).

The Legacy of Komitas Catholicos

Beside the “Seal of Faith” and “The Book of Letters,” Catholicos Komitas has left two authentic and supreme legacies: The Church of St. Hripsimeh in Etchmiadzin, built by him in 618, which up to this date stands miraculously as the most authentic and unique sample of the Armenian Church architecture, and the Hymn known as “Antzink nviryalk sirooyn Krisdosi,” (Souls dedicated to the love of Christ), written by him in 36 stanzas according to the alphabet of the Armenian language, dedicated to the memory of the Roman Virgins Hripsimyank and Gayanyank and their companions, who were the first martyrs to witness Christ after being persecuted by the Roman Emperor, and upon arrival to Armenia were martyred by King Trdat III Arshakuni (298-330), by the orders of the Emperor. The hymn is the oldest verifiable hymn by author and date in the entire Hymnbook of the Armenian Church, a volume which was gradually compiled and completed in the span of 1000 years, from the 5th to the 15th centuries.

The Armenian Church and nation is forever grateful to Catholicos Komitas and Bishop Karapet Ter Mkrtchyan for the three-fold legacy beyond any reservation: The Seal of Faith, the Church of St. Hripsimeh, and the Hymn dedicated to their memories. In recent years a musicologist Krikor Pidedgian wrote an important book on the Hymn giving an in-depth and complete analysis of the 36 stanzas historically and from the musical point of view. Pidedgian has made an educated comparison with similar hymns that are composed on the same musical mode, after the style of the Armenian Church music.

“NAREK” “BOOK OF LAMENTATION”

In Modern Armenian

Ten Centennial

(951-1951)

Ten Centennial

The year 1951 marked the 1000th jubilee year of the birth of the leading Armenian monk St. Gregory of Narek, born in Vaspurakan in 951, the son of Bishop Khosrov Antsevatsi, a great scholar and a famous teacher himself who wrote the first extensive Commentary on the Daily Worship Services of the Armenian Church, published once in Constantinople in 1840. St. Gregory left his great legacy, his famous “Book of Narek,” better known as the “Book of Lamentation,” a book of personal prayers of highest integrity. The 1000th year was solemnly observed in October, 1951 in Lebanon under the auspices of His Holiness Karekin I Hovsepiants of the Great House of Cilicia. I remember the celebration as a student in the Seminary of Antelias and the praiseworthy panegyrics delivered by Archbishop Yeghishe Derderian of Jerusalem, the poet Yeghivart, and His Holiness the Catholicos of Cilicia. The same year, as I recall, the 1500th anniversary of the Battle of Vartanants (451) was also marked worldwide and upon the recommendation of Catholicos Karekin I Hovsepiants a solemn oratorio, “Khorhourt Vartanants” (words by poet Vahan Tekeyan), was composed and conducted by the distinguished composer Hampartsoum Berberian, our teacher.

The Translations of “Narek”

In 1926, the first authentic translation of St. Gregory of Narek’s unprecedented “Book of Lamentation” (matyan voghbergutyan), was translated from the classical Armenian to the vernacular by Archbishop Torkom Koushagian. Later, the same difficult task was undertaken by Archbishop Karekin Khachadourian, both well known and brilliant graduates of the Seminary of Armash, near Constantinople. The first was published in Cairo, where Koushagian, a senior of his colleague, served as Primate of the Diocese of Egypt, and the second in Buenos Aires in 1948, where Khachadourian served as the Legate of the Catholicos of All Armenians. Prior to 1926, the pioneer of the translation into modern Armenian in Constantinople was Missak Kochounian (Kassim) in 1902.

One thousand years had gone by and the most intricate “NAREK,” written in unusually high and literal style, was widely read in Classical Armenian, but only few understood the powerful and lengthy devotional prayers. The book was so close but still “away” from the people, the faithful, and even the scholars. The task was a delayed necessity, since the original vocabulary and the expressions in between long and poetic sentences had to be “re-written” by qualified clergy. Both archbishops have kept the standard high where the “Book of Lamentation” should stand with competence and patience. They occupied the Patriarchal Sees of Jerusalem and Constantinople respectively. Patriarch Torkom Koushagian passed away in Jerusalem in 1939, and Patriarch Karekin Khachadourian passed away in Istanbul in 1961.

The title of Archbishop Koushagian’s translation was “Prayers of St. Gregory of Narek,” specifying his work as “rendering into modern Armenian,” in a volume of 20 pages in-depth Introduction alone and 367 pages of the text. Archbishop Khachadourian put his talents and efforts together to translate the text in poetic verses, with facing pages in the original and the vernacular. Later Armenian translations were attempted by scholars in Soviet Armenia, and also in foreign languages, such as French and English, following the two basic renditions.

The Content

“Narek” is a literary unit of high quality exclusively for prayers on one to one basis with the Creator God. It is indeed a miraculous book, for the Armenian Church second to the Holy Bible, full of deep knowledge of the Holy Scriptures, relating it to the individual on a much higher personal and psychological orders of the believer. It is addressed to God Almighty “From the depth of the heart conversing with God,” a repeated supplication at the opening of each prayer. The prayers are addressed to God by the individual in the first person singular as sinful and fallen, but with the hope of being lifted up by the mercy of God. In total they comprise 95 lengthy prayers, some of them specifically powerful to heal, followed by the texts of the healing miracles performed by the Lord Jesus Christ, quoted from the Four Gospels.

It is amazing that a short colophon survives written by the hands of the author St. Gregory of Narek himself. The colophon is shown below with additional material and indexes to the publication of 1858, a rare edition. This edition is a valuable volume in my library. Most probably both translations were rendered from this edition.

The Translators

Both eminent translators into the vernacular admittedly and for sure were masters of the Classical Armenian, especially when penetrating into the style of the author St. Gregory, deeply religious, high in literary and poetic style. They were capable revealing the hidden sentiments eloquently uttered by the Saint, making sure the translators not to distance themselves from the original, while gradually approaching the borders of the vernacular. Both Eminent Archbishops, later Patriarchs of the Armenian Church, have successfully translated the “Narek,” displaying their talent, knowledge and patience to make the book understandable, and not merely simplify it, but mostly displaying the physical and psychological relation of the believer with the Creator.

St. Gregory had the talent to use masterfully both poetry and prose which made the task of the translators that much intricate. The fact that both translators had already deployed the art of poetry, while otherwise producing lasting literary works in forms of sermons and religious poetry, were the only graceful scholars who could handle the task and promote the translation of “Narek.”

The Old Edition of 1858

In my library this ancient and rare edition of “Narek,” printed in Constantinople in 1858, is enriched with a number of valuable features. The title reads “Book of lamentation by Gregory the monk of the Monastery of Narek.” It is in its original leather cover, printed during the pontificate of Matthew I, Catholicos of All Armenians, and contains 368 pages. Additional panegyric is included in this edition by Arakel Vardapet in the form of poesy with 36 stanzas, following the Armenian alphabets, from A to K, praising St. Gregory of Narek. This portion unfortunately is left unnoticed by the translators and therefore is unknown to the readers of the book. The text is partitioned clearly, using the finest Armenian fonts of the time. In addition, it follows by the original colophon giving the name of the scribe, St. Gregory himself, and the place the manuscript was written. Also a dictionary explaining over one hundred of difficult words found in the book. The original colophon reads:

“I, Gregory the monastic priest, the last among the writers and the junior among the teachers, with the collaboration of my dear brother Hovhannes, a member of the eminent and glorious monastery of Narek.” (pp. 296-297).

A later colophon reads:

“In memory of saintly and eloquent St. Gregory, who studied to become an ordained cleric in the monastery of Narek, where he was assigned prelate and whence he became the famous Narekatsi.” (pp. 297).

In the second colophon St. Gregory’s other commentaries are clearly mentioned as follows: “Commentary of Solomon’s Song of Songs”, “Sermon on the Cross”, “Eulogy on St. Mary the Mother of God”, “Eulogy on the Apostles”, “Eulogy on James, Bishop of Nisibis”, “Sermons and psalmodies.”

It further continues giving more information on the Monastery and the death of St. Gragory of Narek at age 52:

“These 95 prayers he wrote eloquently upon the request of his fellow monks, and left his legacy from his immense knowledge. He passed away and returned to the Creator at his young age in the year 452 according to the Armenian Calendar (+551)=1003 AD, and was buried in the Monastery of Narek.”

“And when King Senekerim moved his domain to Lesser Armenia, the monks of the Monastery of Narek transferred the honorable body of the Saint into the region of Akn and Tiurik. As of today the site is in ruins and is called Arak, a place of pilgrimage, whence healings are reported for the Glory of God.”

Additional Articles

At the end of 1858 edition the following five articles appear:

- “Eulogy of St. Gregory addressed to St. Mary” (pp. 298-314)

- Prayer of Mkhitar Gosh (12the c.) “On the Holy Eucharist” (pp. 314-319)

- “Panegyric addressed to St. Naregatsi” by Arakel Vardapet (pp. 319-322)

- Miracles from Gospel readings (pp. 323-350)

- Dictionary of difficult words (pp. 351-368).

“FOURTEEN GENERATIONS”

The Silver Star on the Spot of the

Manger in Bethlehem

With Its 14 Points

The Star on the Manger

Curiosity sometimes proves educational. In this case it was for sure. Recently I learned something important as I was asked by Mr. Harold Mgrublian, a dedicated member of the Los Angeles Armenian community and the Vice-Chairman of the Ararat Home for the Aged for many years, if I knew anything about the Star of the Manger and its 14 points or rays, as to why they were that number and not less or more. My answer was simply this: “I have been in Bethlehem and even performed Holy Mass exactly over the Manger many years ago on Christmas Eve of 1955, on the orders of the Acting Patriarch, Archbishop Yeghishe Derderian, and had seen the wide spread impressive Star, but never thought about counting the points.” Harold, while visiting Bethlehem with his wife Alice, himself a retired engineer of metallurgy, was impressed by the Star and counted the points. They were 14. He was curious to know why fourteen.

Asking the question to the local Armenian and Greek priests in Bethlehem if they knew the answer, he was hopeless. They had no idea, nor were they interested in it. Upon his return to the hotel in Jerusalem, Mr. Mgrublian asked about the “number” and was told to see a certain historian who could help him. The answer was the “Fourteen Generation,” repeated three times in the opening chapter of St. Matthew’s Gospel, marking the descendants from Abraham to King David 14 generations, and from David to the Babylonian Exile 14 generations, and from the Exile to the Birth of Jesus 14 generations.

Harold, the grandson of an Armenian priest, Der Garabed Kahana Mgrublian of Aintab, is an intelligent, interesting, and interested person with sharp memory at his age of 88. He was always involved in many Armenian activities in southern California. He told me about his grandfather’s ordination into the priesthood in 1905 when he went to Sis, Cilicia with other candidates to be ordained by Catholicos Sahak II Khabayan of Cilicia, and upon his return to serve the Armenian Church near Aintab. Harold told me he visited Aintab and went to the village his grandfather Der Garabed Kahana served as a parish priest, and reported with exact locations and names. Harold, an American born, is fluent in Turkish which made his inquiries easier.

Biblical Evidence

Fourteen generations from the Babylonian Exile to the Birth of Jesus. What is the history behind it? Jews were exiled to Babylon three times: in 598 BC, centuries after the Davidic Kingdom, in 587 BC, and finally in 582 BC, with a deportation of a total of some 10,000 people. We read about the exile from Jerusalem to Babylon in Kings II chapters 24 and 25, leaving behind a ruined Temple by the fire, and city’s walls ruined. It was only by the orders of Cyrus II of Assyria that the exiled returned to Jerusalem and restored the Temple in the year 515 BC, marking the end of the exile.

Among those returned was Zerubabbel, a descendant of King David, who assumed the governorate of Jerusalem. He was the grandson of king Jechonias and the son of Salathiel, as we read in the Gospels of Matthew (1:12) and Luke (3:27). He was assisted by Joshua the high priest. Zerubabbel is known as the ancestor of Joseph, the husband of Mary. Prophets were also instrumental in the establishment of the lineage from King David down to Jesus, who prophesied saying: “A virgin will bear a son whose name shall be called Immanuel, meaning God with us.” Among the prophets are prominent Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Zechariah who proclaimed the revelation of God, thus paving the way to the Birth of Jesus in Bethlehem.

The closing verse in Matthew’s Gospel says it all. “Thus, from Abraham to David 14 generations, from David to the Babylonian exile 14 generations, and from the exile in Babylon to Christ 14 generations.” The Evangelist adds immediately the announcement of the Birth of Jesus, saying: “And the Birth of Jesus was as follows.”

Fourteen generations three times are shining through the fourteen rays of the Star of the Manger. Here is a lesson to learn.

15th CENTURY ARMENIAN MANUSCRIPT

In Pasadena

“Book of Sacraments”

The Manuscript

Harut Der Tavitian of Pasadena, Chairman of Nor Serount cultural Society and a leading intellectual, owns a valuable Armenian manuscript which I had the opportunity to study and present the rare book to the scholars of our people. The title of the manuscript, written on paper, is identified by this writer as Book of Sacraments based on its content, since at the beginning and at the end a few pages are fallen. The book is a manual of the Sacraments of the Armenian Church used by priests only, of at least five consecutive generations. The Book of Sacrament is essential for every priest to have it handy to perform the seven Sacraments according to the Armenian Church rites. This manuscript has two additional eulogies, titled as “Lamentation on the Burial of the Boy,” and “Lamentation in memory of the deceased.”

First of all, it was important for me to look for a clue to determine the date and the place where it was written, like many tens of thousands of manuscripts which have survived as of today, and which are known to the scholarship, having been catalogued in various volumes, except for this one manuscript which remained to be searched by an interested scholar. So I tried to find clues for both, date and place, which were almost impossible because of the lack of the first and the last pages. Coincidently as I was reading through the manuscript I saw the above mentioned eulogy on the “burial of the boy” in the form of a poetry dedicated to the young boy who had died at a very tender age.

In the lengthy eulogy given below in translation, I was surprised to see the following sentence: “In the year eight hundred and seventy, plus eight years later” the boy died. This brief and yet most important date can only be the accurate date of the manuscript. The years recorded are in accordance with the Armenian Calendar, which provide the date 870+8=878. To convert the year into Anno Domini, we must add 551 when the Armenian Calendar began. Therefore,

The verified date of the writing of this manuscript is definitely 878+551=1429AD.

The Content

The manuscript contains the services of Matrimony, Burial, Blessing of Water, Washing of the Feet, and the Blessing of the Cross. It is interesting to note that each text is written in its original and native style, quite different from the text printed later for the use of our own generations. This 15th century text is a piece of combination of church and family life, the language being Classical Armenian but sometimes local words are used to make the meaning more sensational. It is surprising however that it does not contain the most important Sacraments of Baptism and Confirmation. This absence is a true surprise, a case which shows the more casual use of the services, rather than purely the canonical sacraments.

The physical condition of the manuscript is poor, the binding very loose, pages missing and later written pages inserted, a case which demonstrate the use by so many successive priests, passing from one hand to another for generations. Page size is 15×10 cm. The manuscript has a value of its own, characteristics for being unique which qualify and even distinguish it from the later publications. It is an ancient document as a source for scholarly research. In terms of artistic illustrations, the book does not qualify, except for some bird-style colored letters here and there for decoration. The creation of the manuscript is local and higher arts of handwriting are not reflected in it, unlike centuries before when the schools in Cilicia produced the highest art of manuscript illustrations on parchment. No information of owners are found, except for a name, and the only name, on the margin as “Baron Khachadour Bagh”(tasarian) added much later, stating the use of the book in Tehran, Iran.

Two Important Eulogies

As said earlier two “lamentations” are the specifics of this manuscript: the “Lamentation in memory of the deceased,” and “Lamentation for the burial of the boy.” Both of them appear for the first and the only time. No Books of Sacraments of later editions include them, which I will refer for future studies. They are local and private, therefore no one would be interested to include in later publications. I believe my translation from the Armenian original stands the first to be published in this article. Some years ago I had sent both original texts with a lengthy description of this manuscript to the late Patriarch Torkom Manoogian of Jerusalem who published them for the first time in SION, theofficialmonthly of the Armenian Patriarchate. The following are the texts in translation, realizing that any translation cannot reflect the real emotional nature of the original language, especially when it refers to the death of a young boy.

“For the Burial of the Deceased”

Ye all priests and theologian doctors,

And the entire faithful people,

Hear my complaints all in unison,

And plead God for my salvation.

Yesterday I thought I was immortal and sound,

Today the message of death arrived to leave,

Telling I have no part in this changing world,

Come back to your eternal paternal home.

Yesterday I was like fortress with my lavish body,

Today they took me out of my dwelling,

To bury me in the grave where dark rules forever,

Having no remedy to return back home.

“For the Burial of the Boy”

The Creator of all creatures was angry at us,

The sweet nature of divinity turned bitter to us,

The fiery sword spread down today,

The fire inflamed from the divine abode.

Woe thousand times to what just happened,

The newlywed bride and groom separated,

Since a child sorrowfully turned to dust,

And since the dead son’s mother grieved deeply.

Sinless boys are stricken by the angel,

Tumbling in front of the parents with compassion,

Fainting pitiable in the bosom of the mother,

And fading away like springtime flower.

The beautiful color faded from his face,

The lights of those oceanic eyes were out,

The handsome and strong arms were tied,

The gold and silver marbles of the bracelet fell,

In the year eight hundred plus eight years,

Bitter grief befell and divine devastation

Made all deeply hurt, weeping to no end.