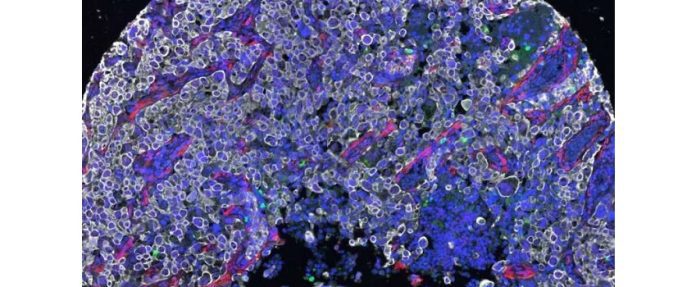

Tumor cells are known to be good at evading the human immune system: they erect physical walls, camouflage themselves, and constrain the immune system with molecular tricks. Researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, have developed a drug that overcomes some of these barriers by tagging cancer cells for destruction by the immune system.

The new therapy, described in the journal Cancer Cell, brings a mutated version of the KRAS protein to the surface of cancer cells, where the drug-KRAS complex acts as a signal to kill. Immunotherapy can then induce the immune system to effectively destroy all cells with this signal.

KRAS mutations occur in about a quarter of all tumors, making them one of the most common gene mutations in cancer. Mutated KRAS is also the target of sotorasib, which the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has pre-approved for use in lung cancer.

The immune system usually recognizes foreign cells by the unusual proteins that protrude on their surface. But when it comes to cancer cells, few unique proteins are found on their exterior, and the immune system cannot detect them.

For years, KRAS was considered untreatable. But in recent decades, scientists have conducted a detailed analysis of the protein and discovered a hidden pocket in mutated KRAS that could block the drug. His work contributed to the development and approval of sotorasib.

However, sotorasib does not help all patients with KRAS mutations, and some of the tumors it shrinks begin to grow again. Scientists wondered if there was another way to affect KRAS.

In the new work, the team showed that when ARS1620, a targeted anti-KRAS drug similar to sotorasib, binds to mutated KRAS, it doesn’t just block KRAS from affecting tumor growth. It also makes the cell recognize the ARS1620-KRAS complex as a foreign molecule.

This means that the cell processes the protein and moves it to its surface as a kill signal to the immune system.